How To Run: Perfect Your Technique To Get Faster And More Resilient

Use this expert advice from technique coach Shane Benzie to refine your running

If you’ve been running for a long time, or even just a few weeks, you might take offence at the idea you’re doing it at all wrong. You’re putting one foot in front of the other and moving forwards faster than walking pace (we hope) – that’s running, right? But if you are prepared to look at your technique and how it might be improved, you can boost your performance while also reducing your risk of injury.

Shane Benzie is a running technique coach and the author of The Lost Art Of Running, which details his experiences in the sport and provides a practical framework for perfecting your gait. That framework also finds expression on Benzie’s online service Running Reborn, where you can sign up for step-by-step videos and other tools to help you change your running technique for the better.

We spoke to Benzie for more general advice about running technique and the first steps you can take if you are interested in changing the way you run.

Why is running technique important?

There’s two big reasons to work on your running technique. One is to avoid injury. Pretty much every runner develops some kind of niggle or injury every year. That’s generally because when we’re running we have around 2.5 times our bodyweight coming back at us when we hit the ground. If we don’t load our body efficiently, that impact does come back to get us.

If we do load the body well, that impact is dissipated, and turns into elastic energy and throws us forwards. We can turn what is sometimes a negative thing into a real positive. Good, efficient movement loads the body well and strengthens the body through movement. If you run well, you create a body that’s fit for the task of running.

Then there’s performance. If we move well and harness the impact we create when we hit the ground, then our performance can go through the roof.

What are common problems with running technique?

One of the big ones is foot contact. I’ve worked with over 3,000 runners one-to-one and I’ve seen 84% of those heelstriking on a relatively straight leg. If we heelstrike we create instability and the foot doesn’t dissipate the impact.

Get the Coach Newsletter

Sign up for workout ideas, training advice, reviews of the latest gear and more.

Where the foot lands in relationship to our body also determines how much we decelerate. If our heel lands out in front of us with a straight leg, that has a big slowing effect as well.

There’s this big thing in running where people say if it’s not broken, don’t fix it. But there is no doubt that using what I call a tripod landing will reduce your ground contact time. It will also give you more stability, so everything above the foot doesn’t have to create that stability. If you lead with the heel, you’re landing on one point of a tripod.

What is a tripod landing?

The tripod landing is three points on the foot: the calcaneus (heel), just under the ball of the big toe, and then a point just under the little toe. It’s essentially those three points coming down at the same time. That way we maximise stability.

See related

- The Basics Of Running Technique Explained

- How To Improve Your Running Form

- Common Running Injuries And What To Do About Them

Is there an ideal cadence to run at?

Cadence is fascinating. It’s the running dynamic we’ve all been able to monitor for the longest, but it’s kind of been hijacked as a way to correct your running form. I believe cadence should be about joining in with the elastic frequency of the body. By this I mean if you run at a cadence of between 175 and 185 strides per minute, you hit the ground, create a load of elastic energy and store it as you move through the stride, and as your foot leaves the ground that elastic energy fires. Outside of that 175-185 zone you move away from maximising that elastic energy.

Should people who have a higher cadence than 185 try to reduce it?

If this elastic frequency thing is correct, and I believe it is, we’d never really want to be out of that 175-185 range. Your cadence will go up when you go faster, but it shouldn’t be the main means of going faster, stride length should be. So if you were running a marathon you might run at a 180 cadence with a 1.3m stride length. If you were doing a 5K, you might run at a 180 cadence with a 1.5m stride length, and if you were doing 100 miles you’d have a 180 cadence and a stride length of 1m.

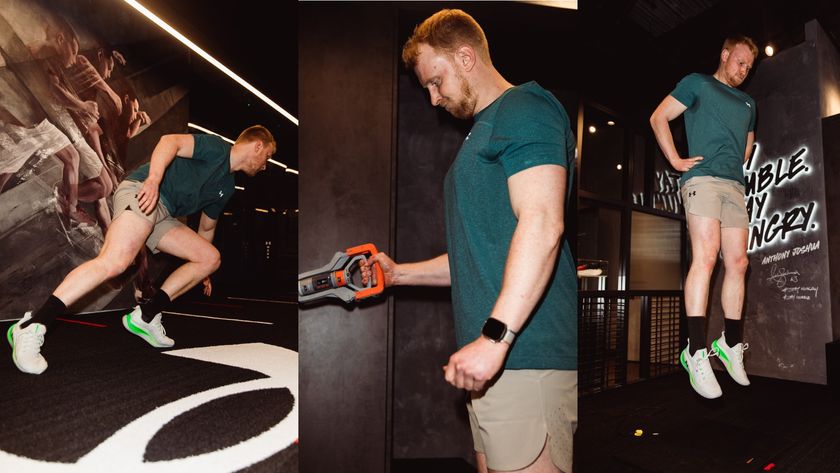

If you’re analysing your technique with a view to changing it, where should you start?

I use some very expensive tech when I’m coaching, researching and analysing, but probably the most powerful thing I use is video. So you need nothing more technical than your phone, and ideally a buddy to film you. If you video yourself from the side, back and front running at two different speeds, it would take five minutes and you’d have a really good record of how you move. I can guarantee it will be different from how you think you do!

I’m really passionate about people videoing themselves. It’s what our site is going to focus on – getting people to buddy up and video each other running, and then be able to go through the video library in the site and see what they’re doing well, what they’re not doing so well, and work on that.

Should you use running watches or other tech that analyses your running technique?

When it comes to running dynamics you can get some incredible information like ground contact time, vertical oscillation, stride length, cadence and vertical ratio on devices which don’t cost a huge amount of money. My one big message is don’t let the data tell you how to run – it should tell you how you ran. You need to have a good idea of what you want to achieve, and the device won’t know that.

The Lost Art of Running: A Journey to Rediscover the Forgotten Essence of Human Movement

You can sign up to the Running Reborn service for £30 a year, with one-to-one coaching with Benzie also available

Nick Harris-Fry is a journalist who has been covering health and fitness since 2015. Nick is an avid runner, covering 70-110km a week, which gives him ample opportunity to test a wide range of running shoes and running gear. He is also the chief tester for fitness trackers and running watches, treadmills and exercise bikes, and workout headphones.