What Is Cortisol And How Do You Maintain Healthy Levels?

A new rapid saliva test makes measuring cortisol easier than ever, so how can knowing your levels help you?

Elite athletes have long gone to great lengths to get detailed information about what’s going on in their body through lab testing and other methods. Wearables and other tech have made much of this available to the average person as well: almost every fitness tracker will now measure your heart rate variability, patches paired with software like Supersapiens can keep tabs on your blood glucose, and Lumen can even see what your metabolism is doing.

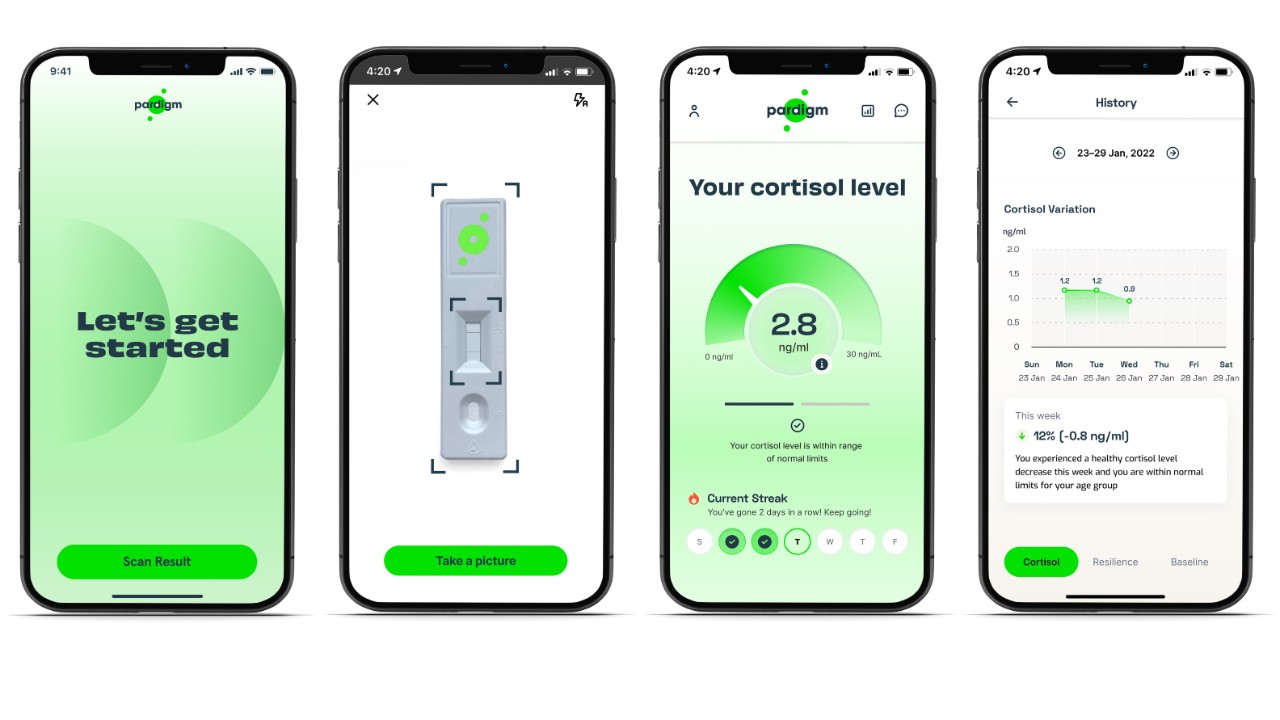

The next frontier might be tracking your cortisol levels as a way to monitor the stress being placed on your body, whether that’s through exercise or the day-to-day challenges of life. Pardigm.com has launched a rapid saliva test in the US to measure cortisol.

For more information on what cortisol is and why it matters, we spoke to Chris McLellan, a professor of sports science at the University of Southern Queensland and member of the scientific advisory board for Pardigm.com.

What is cortisol?

Cortisol is the most well-known stress hormone. It's a glucocorticoid that's synthesised from cholesterol, and it’s produced by an area in the adrenal cortex, which sits within the adrenal glands on the kidneys.

It’s a really important hormone that does much more than being related to the stress response. Its primary role is to mobilise glucose to give you energy to get up and move, and react to whatever a situation might be. It’s really important for normal daily function.

What causes cortisol levels to change?

Cortisol will respond to a whole lot of things that happen in the day – exercise, a stressful situation at work, or even nutrition. It’s a diurnal hormone, which means it fluctuates throughout the day.

There’s the cortisol awakening response, which is really important. That’s the difference between someone who may wake up and jump out of bed – we assume their cortisol is pretty good – and someone who feels more fatigued when they wake up than they did when they went to bed. That’s a fair indicator that a person’s cortisol awakening response is compromised.

Normally, we see a cortisol spike until around the middle of the day or late morning, and then we’ll see it gradually drop off until the late evening when we’re starting to prepare for bed. It should be at its lowest level just before you go to sleep. You don’t want high cortisol then, because that’s switching on your glucose metabolism and giving you energy.

Cortisol can be affected by physical stress, like exercise, and it’s also impacted by psychological stress and how we perceive our stress. A little bit of stress is good for us, but too much of a good thing often becomes a pretty bad thing.

Get the Coach Newsletter

Sign up for workout ideas, training advice, reviews of the latest gear and more.

What are the downsides of having high cortisol levels?

The key negative is much like that of insulin, with metabolic diseases and diabetes where people become insulin resistant. We can see a similar pattern with cortisol where if it is chronically elevated over a long period of time, we can see dysfunction and ultimately, cortisol resistance. That means its ability to mobilise glucose and to play those roles in the body becomes compromised. Then we see a lack of energy. People are exhausted and they feel run-down all the time.

One of the other negatives is around bodyweight and body mass. Cortisol will enhance what’s called lipolysis, which is an increase in triglyceride uptake. That means it’s much easier to gain weight, and much harder to lose weight. So it’s much easier to gain weight when you’re highly stressed, and if your diet is also crappy at the same time, you can gain weight quickly.

Do different types of exercise produce different cortisol responses?

It’s based on intensity and volume. For example, running would produce a higher cortisol response than a traditional weight-training session in the gym, where you might do a set of the bench press, and then you’ll have a few minutes rest, and then you might do another set. Your heart rate doesn’t get that elevated, the stressors on the cardiovascular system aren’t as high, and therefore we get less cortisol.

So long-distance runners, and anyone that’s training a lot every day at a high intensity, we will often see their cortisol levels pretty high. If they have their nutrition and recovery on point, then they’ll be perfectly fine, but if not, that’s when things can start to go south pretty quickly.

How do you manage your cortisol levels through your lifestyle?

I’m not a dietitian so I’m hesitant to go into specifics of nutrition. Is there any particular food that can lower cortisol? The answer is no. Is there any particular food that would elevate cortisol? Not on its own, but certainly a poor-quality, high-fat diet, over a period of time would tend to produce a less ideal profile.

Recovery and sleep, and the quality of sleep, are important. If you’ve got really poor sleeping habits, then the likelihood is that you will have a poorer cortisol awakening response. Then that will tend to lend itself to a compromised cortisol profile over time.

Other things are work-life balance, alcohol consumption, those sorts of things. People say you’ve got to take stress out of your life, and you’re like, “How do I do that? I’ve got a mortgage. I’ve got a young family. I’m sleep-deprived. I eat on the run and work a 60-hour week, what do you want me to do?”

Being able to monitor cortisol on the spot gives us some capacity to identify if there is a problem, whether it’s work-life balance, or sleep. Do I eat at 10pm? Am I drinking coffee at night?

How do you measure cortisol?

Up until very recently, it required a blood sample and a lab test. It’s quite a lengthy process that might take several days. That’s of less value to the average person [because] cortisol has a half-life of 66 minutes. It fluctuates frequently throughout the day.

It’s important when monitoring cortisol to be able to get an idea of what someone’s diurnal profile is throughout the day. Once you’ve done it once, you can then test any time of day you like and compare that to the baseline.

Saliva analysis has been well established as being a valid and reliable marker – it compares well with blood. We can use it to monitor individual stress profiles and if athletes are able to monitor their cortisol, we can look at how they are handling their training loads. Are they fully recovered? Are they ready to train again, optimally?

To put it in really simple terms, if you’re looking to measure chronic prolonged stress, cortisol is your go-to. And it doesn’t fluctuate minute by minute, as opposed to, say, heart rate. For me, it is a better marker of overall long-term stress and adaptation to whatever environment we’re in.

Nick Harris-Fry is a journalist who has been covering health and fitness since 2015. Nick is an avid runner, covering 70-110km a week, which gives him ample opportunity to test a wide range of running shoes and running gear. He is also the chief tester for fitness trackers and running watches, treadmills and exercise bikes, and workout headphones.